For me, the act of collecting is all about connections and connecting with particular moments in time. The Festival of Britain (FOB) in 1951 was a significant event that promoted a sense of optimism based on a proposition that innovative industrial design practices were key to building a better world, or at the very least an economic recovery in post-war Britain.

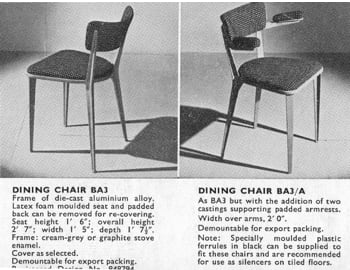

In a corner of our lounge room sits a Robin Day model 658 Moulded Lounge Chair manufactured by Hille and designed by Robin Day in 1951. The chair was originally designed by Day for the Royal Festival Hall at the FOB (see pic) and featured a luxurious copper plated steel finish. After the festival the chair was produced by furniture company Hille, the copper frame replaced with a grey painted steel frame. This particular chair is interesting for a number of reasons, the first being that unlike every other model 658 chair I have seen, this chair has no provision for padded cushion on the back section of the chair. Secondly, the chairs has a Hille badge and is stamped ‘Made in Britain’ on the underside, but there is also a metal badge for ‘John Stuart Inc’, a retailer in the United States. This chair has seen some miles, it has crossed the Atlantic where it was most likely sold at a John Stuart store, then it sat in a lounge room until it was sold in auction in the 2000s, then made it’s way back to Britain, then from Britain to Australia.

Robin Day’s model 658 chair marks an important moment in time, it speaks of a ‘can do’ post-war optimism that sought to take advantage of new technologies and industrial design processes, such as developments in the moulding of plywood and new adhesives that made it possible for designers to redefine our understanding of furniture. The floating moulded ply section of the model 658 chair was made possible through such innovation, a curvaceous piece of moulded with a walnut, mahogany or rosewood veneer balancing delicately on three steel rods attached to the underside of the chair. This is more than a chair for relaxation, this is a chair for taking flight on plywood wings that soar to a place where anything is possible, well so it would seem until problems associated with the design led Hille to discontinue the model 658 and replace it with the less ambitious model 700 chair. To address the issue with stability and wear issues associated with the model 658’s plywood upper section pivoting on only 3 points on the chair, a decision was made to extend the plywood upper section to meet the chair seat.

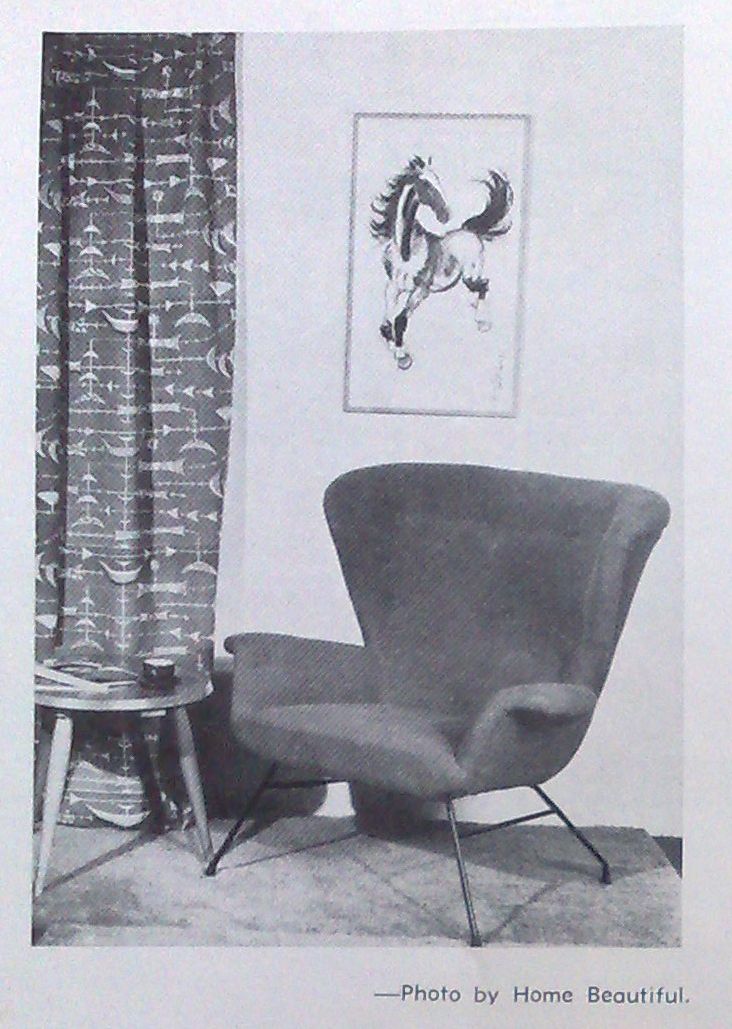

A functional solution to a problem, but the 700 model exhibits none of the majesty of the previous model. Gone are the expansive ply wings floating gracefully on 3 slender metal arms joined to the seat. The 658 Moulded Lounge Chair was an experiment, a magic trick made possible by technological advances in adhesives and ply moulding techniques. The chair was produced from 1951-1955, and represents a small moment in time where optimism, experimentation and creativity aligned to create a chair of outstanding beauty. It’s important to note that design doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and many Australian designers who attended the Festival of Britain in 1951, or sought work in post-war Britain, returned home with many of these revolutionary ideas. British designer Bernard Goss moved from London to Melbourne, Australia in 1951, where he later formed Pandar Furniture with manufacturer William Palstra.

The first of the Pandar Furniture range, consisting of two upholstered chairs with steel rod frames, was launched in 1955. The ‘Caribbean’, a low back arm chair, and the ‘Jamaician’, a high back armchair, are arguably reminiscent of British design of the period. The Caribbean armchair is by far my favourite Pandar design, it reminds me of Robin Day’s model 658 lounge chair, which makes me wonder to what degree Goss’ British heritage influenced his designs for Pandar Furniture in Australia. There were many designers working in Australia during the 1950s, and many of them have been lost to history, but if you take the time to search, you can find some real gems. The Caribbean armchair designed by Bernard Goss and manufactured by William Palstra is a treasure waiting to be discovered.